Walking into a Medieval church that has either preserved its ceiling paintings or restored them can be like entering a completely different dimension of devils and saints, mythological images and depictions of everyday life when the paintings were made.

Unlike the rest of Europe, Swedish churches were built quite late, between the late 11th and early 12th centuries. They were often adorned with rich decorations, and the church paintings we know today span from the early 12th century to the 16th century.

They were painted on the ceilings and walls of the stone churches using lime-based paint. The names of the painters who created the works are often unknown, but some are still alive, such as Johannes Rosenrod and Johannes Iwan.

In the cases where the names of the individual painters do not survive, their works are divided between the Mälardal School and the Tierps School, the latter of which was a style used during the latter part of the 15th century.

Leading the way was the ”Tierpsmästaren,” – the Tierp master – a painter whose name has not survived the centuries, as well as Anders Eriksson, Peter Henriksson, and Peder Jönsson, as well as two painters who today are only known by the names Alfabetsmästaren – The Alphabet master- and Edebomästaren.

But the most famous master of them all during this time, and whose name we know, was Albertus Pictor, or Albertus Pärlstickare (pearl knitter) as he was also called.

Albertus was most likely born in Germany, and in some of the decorative ribbons on his paintings, he called himself Albertus Ymmenhausen and Immenhausen, respectively. However, this has been interpreted more as a hint of his origin than an actual surname.

Unfortunately, it does not make it easier to confidently say where he came from. During his lifetime, several German places had variants of this name. Still, the presumed German is strengthened, among other things, by the presence of Jewish caricatures in his paintings, which was common in Germany at this time, while Sweden, for its part, had no Jewish population.

In the language ribbons with which some of the paintings are decorated, certain ”Germanisms” also appear.

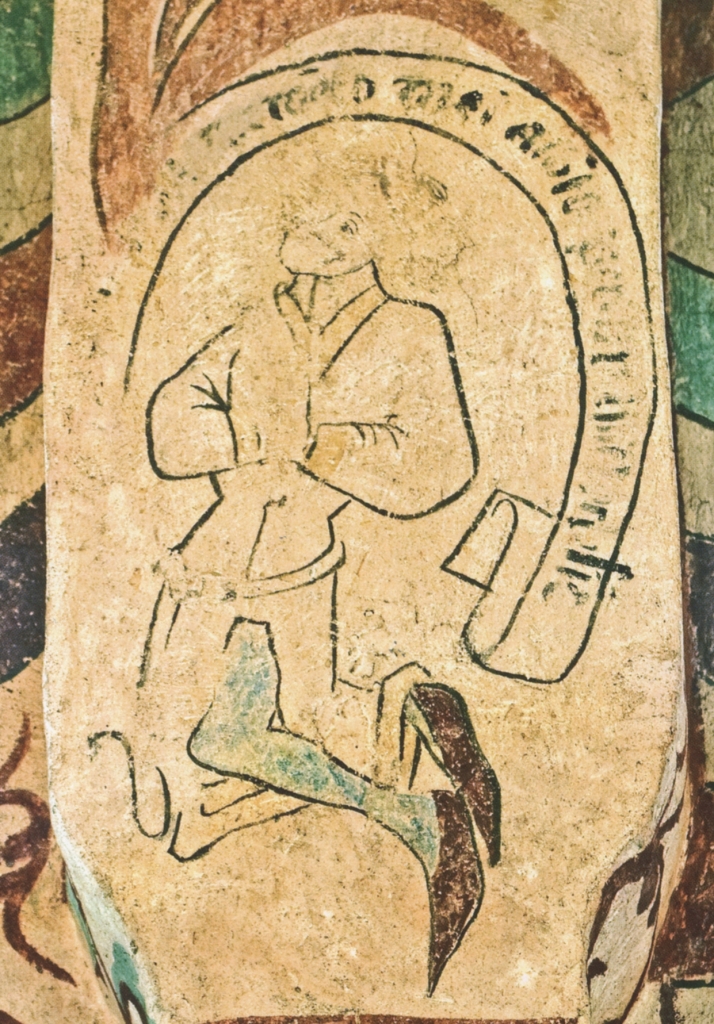

There is a single preserved self-portrait of Albertus Pictor in Lid’s church in Strängnäs diocese. The face in the painting has been destroyed almost as if to preserve the mystery surrounding his identity. But the text tape says, ”Remember me, Albertus, this church’s painter.”

Of course, we ”remember” him, not least through the colourful and multifaceted paintings, which contain everything from nightmarish depictions of hell to humorous mythical creatures.

He is believed to have been born around 1440. Throughout the following decades, immigration from Germany to Sweden was significant, and it was common for artisans to make long journeys to find new places to work. Albertus Pictor may have directed his steps towards Sweden to find work.

One of the many German traders already here may also have recommended him. We know that in 1465, he was in Arboga, and according to the city’s reference book, he was included among the town’s burgess.

This shows that he was already established as a master painter.

In 1479, Albertus Pictor appeared for the first time in Stockholm’s land register, a list of landed property that was the basis for taxation and contained the farm’s location, size, yield, owner’s name and other relevant information.

He was married to Anna, widow of Johan Målare (painter), and according to the register, he also saw Anna’s children receive their inheritance from their father this year.

Marrying the widow of a master painter was advantageous for a newly arrived artisan; it meant he could take over the deceased husband’s place in the town’s guild.

He also gained access to Johan Målare’s workshop and clientele, while Anna and any minor children from her previous marriage could rely on being supported.

There is no indication that Anna and Albertus had children of their own. Maybe Anna was older than Albertus was.

They lived in a house next to the current Parliament building, an address in central medieval Stockholm worthy of such a distinguished church painter as Pictor.

According to the tax records and the so-called Scots books, he was a painter and a pearl embroiderer.

This craft involved sewing and embroidering with gold thread and pearls. It was mainly used to decorate church robes, altar cloths, and ceremonial clothing. Flags and banners also would have been commissioned.

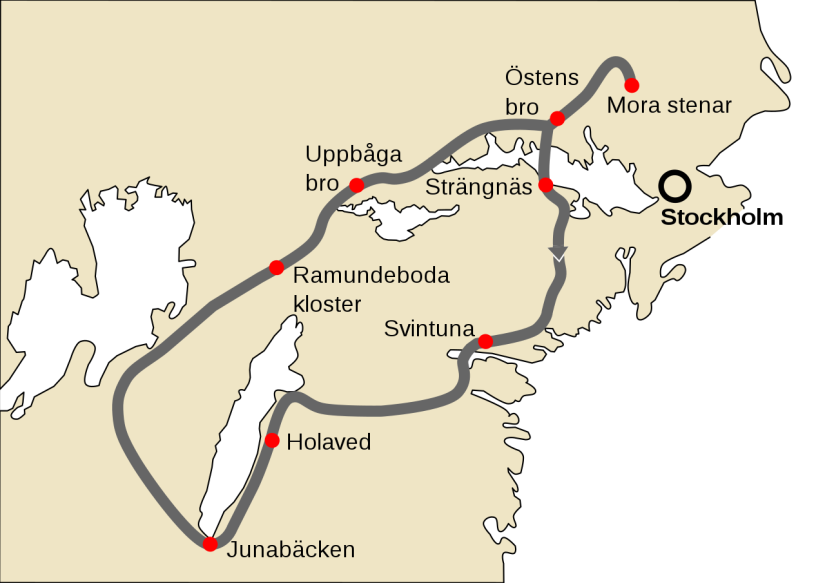

During the years he was active as a church painter, he primarily worked in the Mälar Valley, with a detour to churches in Norrbotten and Nederluleå, where Albertus Pictor, or someone from his workshop, is believed to have done the ceiling paintings sometime in the 1490s.

Just as Michelangelo did not personally paint everything attributed to him in Rome, neither did Pictor.

Instead, the master artisans had apprentices who worked according to the manner, motifs, and colouring the master instructed them to follow.

Today, 37 churches are considered to have paintings by Albertus Pictor, most of them in Uppland, where Uppsala Cathedral is one of them. Even the tiny church in the shadow of the cathedral, the Trinity Church, has paintings by Pictor.

Art scholars who have studied him, such as Pia Melin, believe that the combination of quality and quantity that Pictor exhibited during his active years makes him unique in Swedish church painting.

A difference noted between Albertus Pictor’s work and that of the contemporary painters mentioned is a lively and moving expression, with highlights and shadows, and not least the fact that the faces of the figures are both individual and anatomically correct.

He also used more pigments than usual, layered the paint, and used different tinted glazes. This technique is mainly recognized in Germany, and the techniques he brought to the art of church painting are what have made him unique among his peers.

His paintings have left their mark on contemporary cultural expressions. The most famous is probably the knight who plays chess with death in Ingmar Bergman’s film ”The Seventh Seal.”

The original, if you may, can be viewed in Täby church in Uppland.

Between 1479 and 1508, Albertus Pictor is mentioned in Stockholm’s reference books at least ten times, often in connection with various disputes.

In 1507, it was recorded that he was sick and bedridden, and after 1509, he was never mentioned again. Sometime during those two years, the master painter passed away.

Sources:

Albertus Pictor – Erik Lundberg

Albertus Ymmenhusen alias Albertus Pictor – Thomas Hall/Fornvännen 2003

Svenskt biografiskt lexikon (Swedish biograpical lexicon) – J.

Roosval

Albertus Pictor: bilder i urval samt studier och

analyser/kriterier för attributeringar av målningssviterna – Pia Melin

(selected images and studies)

Härkebergas rika skrud: möte med målaren Albertus Pictor –

Harlin, Tord; Norström Bengt Z., Bergman Sten,

Davidson Nikolaus von

Images:

Härkeberga church – Kevin Cho/Creative Commons

Jonas devoured by the whale – Lars-Olof Albertsson/Creative Commons

Remember me….. – Creative Commons

Dance around the golden calf – Creative Commons

Vaults – Max Ronnersjö/Creative Commons

Death plays chess – Håkan Svensson/Creative Commons